George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards multi-author shared-world universe has been thrilling readers for over 25 years. Now, in addition to overseeing the ongoing publication of new Wild Cards books (like 2011’s Fort Freak, Martin is also commissioning and editing new Wild Cards stories for publication on Tor.com. Paul Cornell’s “The Elephant in the Room” is the tale of a young woman who can temporarily take on the superpowers of people she’s near…and of the crisis this leads her into as she struggles to deal with an overcontrolling mother, a very strange boyfriend, and the beginning of a career.

This novelette was acquired and edited for Tor.com by George R. R. Martin.

“My dear,” said my mother, “when your father told me you’d joined the circus and would be turning into an elephant, I had to come over immediately.”

And I suppose that was true.

Mum, you see, on hearing about my biggest, though perhaps not my most prestigious, theatrical gig thus far, had decided, to my horror, to come to New York. Dad had stayed home, thank goodness. He was probably looking forward to enjoying his shed. But Mum, on being told that the New York School for the Performing Arts had placed me with the prestigious Big Apple Circus, had darted across the Atlantic like a salmon. Sorry, I should be more specific. I’m still, I suppose, not quite used to living amongst . . . I mean living as part of . . . a community who have special, you know, powers. So I should emphasize that that was a simile. My mother cannot turn into a salmon. (That is, I suppose, one of the little-talked-of features of living in a neighborhood like New York’s Jokertown, where someone of one’s acquaintance might actually go green with envy or fall to pieces: One has to indicate where the line of metaphor is drawn.)

I’m making this all sound so very lighthearted, aren’t I?

I met Mum at JFK in the company of Maxine, a Jokertown Yellow Cab driver of my acquaintance who really drives her vehicle. That is to say, she runs it off her own calorie intake. This, if one can do it, is, apparently, a good deal, economically. It means that Maxine is happy to be paid in junk food, which also makes economic sense for her passengers, and makes hers the hack that jokers and poor drama students head for after the show, with a bag of White Palace and fries for change. This ability came to her suddenly, when she was a child, when she was involved in a frightening car accident, and, in that extraordinary way which makes it very clear that our brains know our bodies better than we do, managed to turn the birthday meal she’d just eaten with her loving parents into a sudden burst of automotive power that saved their lives. Long term, however, it meant she lost her family. Within the year, actually. Because that moment she used her, you know, power for the first time was also the moment she . . . changed. They couldn’t deal. They put her up for adoption. Nobody took her. You get a lot of stories out of those children’s homes that got packed with ace and joker kids back then. These days, they’re the stuff of Young Adult novels, but I bet the truth of it was even more grim. People understand, to some degree, the original release of the Wild Card virus in September 1946. They feel for the first generation of those infected, be they powerful ace or differently bodied joker. They feel the loss of those who “drew the black queen” and died on the spot. They feel for the deformed and stillborn children of those infected. They’re not quite as able to categorize their emotions for those of us unlucky enough to get infected in subsequent decades. The virus is still out there in the jet stream. It’s been found on every continent. (At some point in my childhood it must have been drifting through rural Dorset.) Maxine, at the moment she expressed it, changed into, and now looks like . . . well, a pile of rubber tires with a pair of googly eyes on top. Okay, yes, you know, like that advertising character. I’ve never said it out loud within earshot of her. That would be cruel. She makes reference to it every now and then, a nod out of the window when we pass a hoarding: “That’s my Dad.” She says tourists who’ve come to gawk at the jokers sometimes go, “No, really?!”

My mother, however, rolled her luggage on wheels to the edge of the sidewalk in the airport pick-up area, and when Maxine got out of the cab to help her with it, went way beyond any awkwardness and into the land of outright social horror. She saw Maxine and screamed.

I had to basically wrestle her into the cab, while looking desperately around to make sure there weren’t any jokers about who might be offended. Maxine was silent all through the journey back, while Mum was a stream of “Honestly, darling, you can’t blame me, we don’t have jokers in Dorset. I thought I was dreaming. I was prepared for your joker friends to be horrifyingly ugly monsters, not, I’m sure charming, if rather disconcerting, giant, blobby, vastly flexible, to fit in that seat up front, I mean you must be . . .” And this was all without the slightest forensic trace of guilt, as if we all yelled about this stuff all the time at the top of our voices in Jokertown.

“Maxine doesn’t self-identify as a joker,” I told her, my voice already a hiss. “She thinks of herself as an ace: someone with useful powers.”

“Ah, of course, because jokers are your actual monsters,” said Mum, “who can’t do anything useful.”

I stared at her, once again horrified by the prospect of taking this woman into my ghetto. “Except . . . sometimes they can, and very few of them self-identify as monsters—”

“So it’s all a bit of a mess, classification-wise? How very American, not to have proper names for what things are. And what is this ‘self-identify’ business you keep on about?”

“It’s about how they want to see themselves!”

“Darling,” she said, “I’d like to see myself as Keira Knightley, but it’s what the world sees that matters, isn’t it? Hey, with your own, you know—”

“My powers.”

“Yes, yes, well, you’ll be picking up a bit of Maxine’s power, won’t you, how did you put it? ‘Like hi-fi’?”

“Wi-fi.”

“Yes, that! I mean you’ll be sort of automatically catching on to what she’s doing—”

“Unless I stop myself,” I emphasized. “I can do that now.”

“Well, well done darling, but don’t stop yourself right now, because surely, if you’re doing it too, you’re contributing to keeping this car moving.” She saw the look of befuddlement on my face and sighed, speaking as if to a toddler. “So you’ll be contributing to the petrol money! I think we should negotiate a discount.” She turned to start doing just that, but before she could I decided I had to put the possibility of being thrown out of the cab before my own comforts and make the ultimate sacrifice.

“Mum,” I asked quickly, “how are my aunts?”

Which immediately distracted her onto her favorite subject, a conversation which was only dangerous to my nerves rather than to my health. My, you know, power, if you haven’t read the reports of what happened, is that I pick up other peoples’ powers (yes, like wi-fi) and start expressing them myself, utterly randomly. Well, until the last few weeks, when, as I said, I’ve managed to gain a level of control. But still, if I’m caught unaware, if, let’s say, an ace passes me in the street, and their power is that they can turn into a pile of goo, well, there I suddenly am, a pile of goo with a sign saying golf sale stuck in it. As happened that one time when I was, erm, between acting engagements. It took all my willpower then to literally pull myself together as the ace, unaware that it was all about proximity for me, and not noticing goo when it was other people, dawdled nearby, getting himself a coffee, passing the time of day. I ran the risk of being lapped up by a small dog, until I managed to rear up at it. And of course, once reintegrated, I was atop my clothes rather than in them. As happens to me rather too often for my taste. My taste in those matters would actually tend toward the not at all.

I’m distracting myself. Like I won’t have to finish this if I do that. Like it won’t have happened, then. Sorry. Anyway. I was able to just about ignore mother’s usual drone about what the aunts were doing back in Dorset, all of which was, as usual, formidably dull. But she segued out of that into her equally doleful round up of cousins and distant relatives the provenance of which remained a mystery, while New York, bloody incredible New York, which she’d never seen before, sailed past the windows like an in-flight movie. I had to lower my own window to get some early autumn air in my face to stay awake. Just as Mum started talking about the sleeping pills which had got her through that terrible flight. She was intending to use them to manage her awful jet lag. I was already feeling that, of Mum and I, only one of us was going to survive the next few days, and that it was going to be me, frankly, because I already wanted to murder her with a crowbar, just bash it across the back of her latest stupid hat, time after time after—

Sorry. I really need to calm down. Just thinking about the start of all this makes me so . . . well, there I am now. I’m angry. Which is better than sad, I suppose. But it’s such an impotent anger. At how things worked out. At how things are. When I don’t think they have to be. They really don’t. No, let’s not go there. Not yet, anyway. Not until I have to.

Sorry. As I think I already said. Many times, probably.

Hello. My name is Abigail Baker.

I am a serious actor.

Until just before the landing of my mother, I’d been having the summer of my life (apart from being arrested and accidentally publicly naked quite a few times during it), working at the Bowery Repertory in Jokertown, the lovely Old Rep, on loan from the School, and making my debut as a stand in. . . . But actually, you may well have read about that, as I said.* It was all over the media, for all the wrong reasons. In the end Mr. Dutton, the theater owner, got a team of lawyers involved, and I didn’t even have to spend a single night behind bars, though I do now, technically, have a criminal record. And, erm, a suspended sentence. Well, several. Anyhow, now the Old Rep’s autumn season was approaching, and with it the end of my placement there, and, having shown me off to the audience in a range of parts that frankly hadn’t stretched my talent to its rawest extremes, Mr. Dutton had, rather too quickly to my mind, agreed to the Circus asking to benefit from my newfound notoriety when it came to my last role before the new school year began.

They actually asked for me. I don’t know if my Mum ever got that, or if it just added to it for her.

Anyway, that was another reason why I wasn’t entirely comfortable with her being in New York. I’d covered up all that unpleasantness, to her, with euphemism, made easier by the positive spin the joker-friendly elements of the media had given it. I’d sent her all the right press cuttings and crossed my fingers about whether or not the sort of newspapers my mother reads would take an interest. That was all I had to worry about. Mum doesn’t do online media. She once, prompted by her favorite columnist, called me up to warn me that Facebook could literally kill me where I stood. As it turned out, she hadn’t ever quite been aware of the me-being-arrested part. She does tend to mention these things if she hears about them. So that was fine. It joined the encyclopedia of details concerning my life of which my mother was unaware. On the day of which I speak, for instance, I had concealed any of my tattoos that might be visible with several layers of foundation.

But there was one big thing I hadn’t told her about. One big thing who, when Maxine angrily thumped Mum’s luggage onto the sidewalk in front of my humble apartment building, was waiting inside. Because he’d insisted. Because he was strung out to the point of distraction and kept grabbing my hands and urging me that since we were together, he wanted my parents to know we were together, wanted them to see he was a good guy. I hadn’t said to him that that wasn’t exactly true. I’d have meant it as a good thing, but right now I didn’t know how he’d take it. I didn’t know how he’d take anything. I looked up at the building, wondering how this was going to go.

“So,” said Mum, completely ignoring Maxine standing there staring at the packet of mints she’d offered her as a fare, “remind me, darling, when’s your first public appearance as an elephant?”

“Tomorrow afternoon,” I said, trying to indicate to Maxine with mere expression that, next time, I’d bring her at least a hamper. “At the matinee. And that’s great, I thought you were going to say something about where I lived.”

“Oh my dear, I wouldn’t dream of hurting you like that. That’s why I said something irrelevant to the moment, you see, to distract us both. But now you’ve spoiled that little act of grace on my part. You never were one for the social niceties.” She glanced back to Maxine. “You know, your friend should come to the circus with you, she’d get straight on the bill. She’d do so well. Bouncy bouncy!” And with an engaging grin, like this was the best idea ever, she actually made a motion like a trampoline.

My mother had told me that she liked circuses. And, she’d said on the phone, also elephants. I didn’t wonder at the time that she’d never mentioned that before. She told me then that she and Dad had met at a circus. That they were there with their parents. I imagined at the time that, with the austerity of Britain in decades past, said Big Top probably consisted of three mice, a spoonful of jam, and a man in an interesting hat. And that my Mum, even at such a young age, would have spent the evening telling my putative Dad at horrifying length about what her mother’s sisters were up to. But now I wonder if that story was even true.

Anyway. Sorry. My expression to Maxine gained several extra dimensions, to the point where I hoped it intimated that next time I saw her I would provide her with nothing short of a feast. Finally, she just shrugged, her arms bouncing off her sides, and got sulkily back into her cab. Mother looked to me with an expression that said her words had once again fallen, inexplicably, on stony ground, and rolled her noisy luggage toward the front door of my block. Where, to my increasing worry, a greater class of horror awaited us.

His name, and I’m pretty sure it’s his real one, is Croyd Crenson. He was infected by the Wild Card virus in 1946, and since the events I mentioned that you might have already read about, with the being arrested and the nudity and everything, he’d been, erm, my boyfriend. He doesn’t look his age. He just looks as if he has ten years or so on me. Okay, maybe twenty. All right, listen, if it was a thing on my part, it was not that much of a thing, compared to being made of rubber or having the ability to reduce oneself to goo. That’s something else I’ve realized about the people who live in Jokertown: Their notion of what’s socially acceptable for nats (sorry, I mean, noninfected people) extends quite a way beyond what’s okay for those living elsewhere. It’s all about what one is surrounded with, what one has as a background to compare oneself to. That, and the low rents, is what makes Jokertown such a vibrant, diverse, Bohemian environment. (That is to say, as Mum would translate it, there are a lot of gay and transsexual people here too. Actually, that’s probably not how she’d translate it.)

But, sorry, I was talking about Croyd Crenson. As I probably will be for the rest of my life, now. Croyd has not always been on the right side of the law. And that was very much the situation that summer. The trouble we’d been in, as you may have read, had a lot to do with his then-current ability to multiply objects (and, luckily for me concerning one particular escape from the police, people) with a touch of his hand. He had been using that for nefarious purposes involving DVDs.

I should have realized that something terrible was approaching (other than my mother) when, three weeks before her anticipated arrival, Croyd had appeared on my doorstep with flowers. They were beautiful, and he looked especially charming with his awkward, sad smile beside the blooms. Though his teeth were chattering even then. Croyd isn’t one for grand romantic gestures. He’s been alive long enough to know that it’s the small things that matter: the way he understands a person, and wants to know about that person, and gives that person, if they’re me, space to talk. And talk. He is, actually, rather the silent type, now I think of it, although maybe that was just because he was with me—

Oh dear. Oh, I’m crying now. Sorry. Sorry. So stupid.

Anyway. Where was I? Right. Right.

That night, he took me out to this backstreet Italian joker place. Its decor was a combination of Sicily and the kind of twisted outsider tattoo-parlor chic that young jokers in New York had developed, that showed up in mainstream design in ways which made you wonder if said jokers were impressed or pissed off. Lady Gaga having the former effect, of course. Her concerts in Jokertown itself, with free admission for jokers, meant she could plaster her videos with orange and purple swirls if she liked. Croyd knew the owner, like he seemed to know everyone dodgy in New York City, so we got a table on our own, and had the food shown to us by the waiters as they sloped or skittered or flapped out to their customers.

Croyd put his hands on the tablecloth and visibly controlled their twitching. He didn’t quite manage to make them stop. The speed of his breathing, in the last few days, had started to worry me. It was all the amphetamines he was taking. Looking back, I’d started to feel nervous around him, not to anticipate his visits with unbridled delight. I could feel him, whenever he put his arm in mine or his hand on my waist, treating me deliberately carefully, like one day he might treat me otherwise. It had started to be like he took a deep breath before I opened my door. But on the flip side of that, the release of that, when I gave him license, in intimate situations, to let all that energy loose . . . yes, well, I think you get the idea.

I suppose he made me feel a lot better about myself. Being with him kind of made one a lady, without anyone ever having to use the word. I hate to say this is true, but I suppose he really was something from the past that I’d tried to escape, that had reached out to me and said I was okay. And at the same time he was something from my new world of jokers and aces, who had helped me to accept being one of that community, to stop standing quite so nervously apart from it. He listened to all my emo bollocks, because, unlike every other man I’d ever met, he seemed to soak up how people felt about one another, seemed to enjoy hearing about it, particularly when it was about me and him. Even when he started to get jittery and raging and paranoid, he still stopped and listened. He made himself do that for me. And he made his own rules, but was nonetheless honorable, outside the law rather than against it, you know, the bad boy thing. But that so minimizes what he was to me.

After dark, we would go for walks in Central Park. People say it’s dangerous at night, but we never felt threatened there. We could always make more trees to hide behind or more stones to throw. Or I could reach out into the brilliant shining city above us and call over someone else’s useful power. We never had to do any of that.

I often think New York feels like it does, natural and full of energy and about and for people, because it reminds us all of something from our evolution: We scurry about at the foot of what seem like enormous trees, and we’ve got this clearing in the middle to rush out into and play and fight and change. You see so many jokers there, day and especially night, like that forest clearing is even there for this latest direction of evolution. And we were jokers too. We were part of the night, and so not threatened by it. We sat on benches, and we talked, or I suppose I did while he looked at me.

I see that look in my memory now. It’s still a good thing.

And then we would go back to my apartment and shag like bunnies. And nobody ever says that at this point in stories, but they really should. They really should.

Oh dear. There I go again. Sorry.

He looked up from his hands, at that table in that restaurant that night. “The thing is, kid,” he said (and I would hate it with a passion if anyone else called me that), “in this next couple of weeks, you don’t know how extreme I’m going to get.”

I watched his hands as I always did, as his fingertips went to absentmindedly stroke the stem of his wine glass, well, not that absentmindedly, or he’d have found himself with several wine glasses. And so would I have, except that I was managing to hold a place in my head back from his now very familiar, very intimate power. “You’ve told me,” I said. “You need the speed to keep you awake—”

“—And I become a different person because of it. Irritable. Cranky. Sometimes . . . terrifying. That’s a word people have used. You haven’t seen that. I haven’t let you see that. Not yet.” I realized with a little jolt that he’d interrupted me. He never did that. “But that’s not what I wanted to talk to you about. You know that next time I go to sleep—”

“You’ll wake with a new . . . you know . . .”

“Power, yeah.” He hadn’t been to sleep since I’d met him. I’d wake up in the night, and he’d be sitting up in bed beside me, reading these terrible 1950s crime novels. He once told me he was trying to catch up with all the books from his youth. “That’s actually what my own power is. Sleeping. Every time I sleep, my DNA gets rewritten by the virus, and I wake up with a new power. But—” He held up a hand to stop me saying I knew all this. “What I haven’t told you is, two other things might happen.”

“You might wake up as a joker?” I guessed.

“Yeah. I might wake up with claws or no face or oozing sores, and you’d have to stop yourself getting those too. How you’d feel about that?”

I actually felt annoyed. I think I got that he was testing me. Although I don’t know how conscious that ever was for him. But at the time I thought I knew everything that was on that table. “I’d still—” And then I quickly changed what I was going to say. Because neither of us had used that word. Yet. “I’d still feel the same way about you. How could you think I wouldn’t? If I’m okay with our joker friends—!”

“Yeah, yeah, but—”

“And if it was that terrible for you, you could just go back to sleep and draw another card, right?”

He paused. He took a deep breath. “Okay, here’s the thing. You might have wondered why I’ve stayed awake so long—”

“I thought you were just finding the duplication thing, you know, useful.”

He laughed. And there was an edge to it. “I don’t want to lose you, Abi. I don’t want to lose you by turning into some horrible monster—”

“But I’ve said you won’t! Don’t say that word!”

“And I don’t want to lose you by dying.”

I stared at him.

“Every time I go to sleep, Abi, I risk drawing the black queen. It’s like playing Russian roulette. One day I won’t wake up. That’s why I stay awake as long as I can before I start hating the way the speed makes me. That’s why this time I’ve stayed awake . . . longer than ever.”

“Because of me.”

“Yeah.” His eyes searched my face.

I hoped I was looking back at him like he needed me to look. I took his hands in mine, and held one of them to my face. If I felt I could have gotten away with it in public, I’d have held it to my breast. “Listen,” I said, “you could get hit by a bus. Or, this being New York, probably a cab. Thank you for telling me the risks. But this changes nothing.”

He smiled. And yet there was something not quite satisfied about that smile. “You’re young,” he said. And then he looked up and realized we hadn’t been served and let go my hand and started yelling for the waiter. We walked in the park that night, but, looking back, it was more like a march.

We didn’t talk about it after that. We both knew where we stood. I found myself accepting the thought that I was a military girlfriend. That my love might vanish forever when he closed his eyes. Or I wonder if I did accept it. I wonder if I got there?

He would arrive at my doorstep with bruises and wave away what happened. “Just some stupid guy, you should see him.”

He would get angry at some memory of the past, pacing and raging, “and then he said, this was in 1962, then he said—!” And then he’d realize I was standing there listening to him in silence, and he would make himself stop, panting.

The worst time was when he went to the window and said he thought he could hear police out there on the ledge. And then he looked at me as if he was using me to check on whether or not what he was saying was sane. And then he broke into a terrible false laugh, and clapped his hands at his own “joke” and headed off, saying he needed a drink, and I didn’t see him for two days and I thought he’d died.

I should have canceled Mum’s visit. If I could. She might have just shown up anyway. It was only because Croyd insisted so hard, insisted like it was a dying man’s last request, that I didn’t. He was trying so desperately to hang on to something. He so needed to be that decent, upright guy for me. I see that now.

Mother walked into the apartment and was confronted by the sight of Croyd, obviously at home there (though he actually wasn’t, we were still in our separate messy apartments), finishing up washing the dishes. Thanks to Maxine’s rage-fueled, literally, driving, we were, I realized, a few minutes early. “Mrs. Baker,” he said, drying his hands and then holding one out to her, keeping it steady through what I could see was sheer willpower. “Croyd Crenson. It’s a pleasure to meet you.”

Mother looked at him as if he were a burglar. At that time, Croyd didn’t look anything other than nat, though maybe there was something a little too intense about those eyes. Even without the drugs. He was wearing a vest and braces, like something glamorous from a 1940s movie, with his hair slicked back. Mum looked to me without taking his hand. “Who’s he?”

I took a deep breath.

“Oh no,” she said.

That sound of genuine anguish and despair in her voice may have been the most terrible thing I ever . . . No, actually, it wasn’t. But at that moment, it was. I looked to Croyd, afraid that he’d be furious. But he’d kept that pleasant, fixed smile on his face.

“Croyd is my . . .” I had been going to say “boyfriend.” But that suddenly seemed such a small, childish word. And the last thing I wanted to feel then was childish. But what? “Lover”? “Partner”?

Croyd didn’t step in to help me. It wasn’t that he was waiting to hear me describe him for the first time. It was, I think, that he realized that if he butted in, it would look like he’d provided the definition, that he had maybe coerced me into that way of seeing things. Holding on to his kindness, on that ledge above such a drop.

“We’re . . . together,” I finished.

Mother turned back to him and looked him up and down. “What are you?” she said, as if she were being shown round the zoo.

“Parched,” said Croyd, “do you want a G&T as much as I do?”

“I mean—”

“I know what you mean.” And that was still so jolly. “What are you?”

“Normal.”

“Well, hey, me too.”

“Oh.” She visibly relaxed, as if she’d been told anything meaningful. “Well, that’s a relief.” And she actually took his hand.

I was about to bellow with righteous anger, but eye contact from Croyd stopped me.

“You’ll have to forgive me,” she said. “I’m just surprised that my daughter never mentioned you.”

“She was worried that you might not approve.”

She smiled so broadly. “I think, actually, I will have that G&T. Now, darling, where are your facilities?”

While she went to the bathroom, I followed Croyd into the alcove I laughingly called a kitchen. “You let her believe—!”

“I will explain the misunderstanding and tell her my true nature. Once she’s got used to me. Okay?” And the tone in his voice, for the first time ever to me, sounded like he didn’t want to hear any arguments.

The Big Apple Circus stands on Eighth and Thirty-Fifth. It’s not that huge a building, but that’s kind of what makes the BAC authentic: It’s a classic, one-ring circus. As I’d discovered, from rehearsing with them for the last few weeks, the joy of actors at their comradeship and tradition, and especially about those situations where they find themselves in a rep company, is to be felt also in the troupe of a serious circus. Clowns aren’t scary when they’ve devoted their life to their craft, and can project helplessness and pathos past their makeup to make kids squeal with laughter that’s about a shared impotence. That fear of them that’s arisen in the last few years: That’s the product of a world that started accepting second-rate clowns. The Big Apple’s joker clowns are especially something to see, not concealing their differences, but using them as props. This isn’t a freak show. It’s about traditional joker skills, used as they’ve been used in circuses since the 1950s. On the morning of my debut, I got to the circus at seven, as usual, for my last rehearsal. Mum had departed for her hotel thankfully early the night before, popping a pill and succumbing to the jet lag I’d so desperately hoped for. Croyd had come to the end of his charming ability to listen to stories the protagonists of which he’d neither met nor heard of. But he’d remained resolutely charming, though I was proud he never nodded at her more ridiculous political assertions.

“Meet me for lunch tomorrow,” she said to him on the way out to her taxi, “and then we can attend Abigail’s debut performance together. I feel we should get to know each other.” He’d agreed and feigned enthusiasm.

But after the door closed, and we’d heard the taxi drive off, he ran at the wall and kicked it, so hard I feared for his toes. “People like that—!” he yelled. “How is she your mother?!”

I told him about how distant I felt from the ancient and immobile forces that Mother represented. How she always tried to control what I did. I reassured him that we’d fooled her, that he’d done fine. And finally, his heart beating through his chest against my palm, he calmed.

I tried to sleep as he tried not to. He was listening on headphones to jazz that I couldn’t help but hear seeping out, as if from some great distance. The man who never slept in the city that did likewise. The saxophone and the little lights way out there finally got into my head and I was unconscious. Which was just as well, because this hadn’t been the greatest preparation for my first performance. But we’d both known it would be like this.

Next morning that taut look on his face was one notch more haunted. “Break a leg,” he said when I was dressed and ready to go. I kissed him. I held him hard. “You too,” I said.

Radha O’Reilly was waiting for me at the performers’ entrance. She looks like a petite, incredibly fit fiftysomething (though I hear she’s a lot older), with the sort of golden biceps that, to my eyes, demand a bit of ink. But that’s not something I ever could say to her, because I’m a bit in awe of her. You’ll appreciate the reasons why: She’s been a famous ace for decades now, Elephant Girl, someone who walked out into the spotlight and declared who she was before there were the ace and joker communities and celebrities of today. She was the first person who turned into an elephant onstage and expected people to see it as entertainment rather than horror. Today I was to be the second.

“Okay this morning?” she said.

What she meant was, was I receiving her power, and was I able to control it? That was why she always met me outside, so we wouldn’t be in a confined space for that moment. I’d been feeling her power from halfway down the street, in that way that I’d used to find so horribly intimate that the first few times I’d come to rehearse I’d been all kind of blushy when I got there. It was true that what we were going to do that afternoon, then that night, then eight times a week was, if anything went wrong, vastly dangerous. But I’d never felt able to ask her if she felt I was the newbie, still likely to mess up, or an actor only trying to be a circus pro, or someone that had been foisted on her, because of my newfound bums-on-seats value, or even if I was any good. She had an utter calm about her that made one both desperately not want to flap around in front of her, and yet more likely to do so at any moment. There goes that language again: Flapping around in front of her was exactly what I was there to do.

I told her I was fine, she finished her none-blacker coffee, and we went inside.

“My mother’s going to be in the audience,” I said, as we stood in the empty ring, me aching all over after the rehearsal.

Radha looked sidelong at me, taking this new factor onboard. Realizing, I think, that I was letting something out by saying it. “Does that add to the pressure?”

“I suppose.”

“Only, I was wondering why you seemed distracted—”

What, distracted enough to dump me at the last moment and send the clown car out a second time? “No! No, there’s . . . you know, stuff going on in my life. But when I’m up there, I’m completely focused.”

She rolled athletically onto her back, and lay there on the sawdust, looking up through the safety net that we knew would be totally inadequate for our own protection this afternoon, but was entirely to make the audience feel that they were watching something only reasonably death defying. “I do this for my mother, you know.”

Feeling a little awkward, I sat stiffly down beside her. “In my case, it’s kind of in spite of.”

“My mother was on the Queen Mary in 1946. The death ship. She was transformed by the virus. She grew thick gray skin. People are still shocked by the pictures of her, but to me that’s just Mum. I never heard her voice. I always wanted to. She’d never recorded herself when she was a nat. Dad stayed with her, while the rest of the world threw up their hands and backed away. They were taken in by this cult, back home in India. You’d see this awkward relationship between Dad and the priests. He loved Chandra, but they worshipped her. She took it, being seen as a kind of holy object, because, well, we needed a home, this was the only place we could live in peace. She had me seven months after the virus. She had a choice in that. Nobody was sure if she would survive the pregnancy. But they wanted me so much, they always told me that. My mother sacrificed so much, without being able to say a word.”

It took me a moment to be able to speak. “That sounds like . . . the opposite of my mother. I think she’d find some . . . horrible words to describe yours.”

“What, you’re setting me up for meeting her today, all the while thinking of her like that?”

“Would you prefer it if I lied?”

“Well, she is your mother. Perhaps she deserves some falsehoods being told on her behalf. None of us can really judge our parents. I don’t believe in karma, but . . .” She shook her head quickly and changed the subject. “I have to introduce you tonight. Have you chosen your ace name?”

“I sometimes think . . . The Understudy.”

She considered it, flatteringly seriously. “I like the humility of that. But you’ll need to know when to become the lead. You’ll need to be strong enough to make that change and have people accept it.”

I felt ridiculously close to tears. I shouldn’t have got into such a serious conversation with everything that was hanging over my head. I needed to keep a distance. “I’m not ready yet. Nowhere near.”

“Not after today?”

“Of course not.”

She nodded, pleased again. “Have you told your mother your real name?”

I couldn’t even shake my head.

“Before we go on,” she said, “decide your name.”

This next part of what happened is something that I can only tell you about secondhand, from what Croyd told me when he called me that afternoon. And yet it’s the most important thing. So you’ll have to accept my memories of his memories. He went over everything several times. The sound of his voice scared me from the moment I took the call. “I have to tell you,” he said, “I have to tell you before you see her again. She swore me to secrecy, and I said yes, I don’t know why I said yes—”

I was frightened that I was talking to someone who wasn’t the man I knew anymore. I also knew, instantly, that she’d done that to him. That the rocklike tradition of what she was had put a hole in him and he was sinking. I said, “Don’t tell me, let me come and see you,” but he started yelling at me that my career was the most important thing, that I had to stay there and get ready, and he made me swear to keep that promise. Finally, I managed to get him to tell me what happened, and here it is, for you, through all the distortions.

He’d taken Mum out for lunch at an excellent diner he knew in Greenwich Village, one where the dodginess was a little more under the surface than usual, and which had, to use his words, “A billion kinds of coffee, cause that always impresses you Brits.”

“I’d just like to say,” he said, holding her chair for her, “I’m charmed by how open-minded you’ve been about your daughter and me. I think she’s a peach.” He frowned at her reaction. “That’s a good thing.”

“You talk,” she said, “like you’re from my father’s generation. Why is that?”

He’d shrugged. He didn’t want to lie again to her, when he’d been going to tell the truth.

“What do you do for a living?”

“Recently I’ve been a DVD wholesaler. Before that, I was an importer. And I’ve been known to dabble in the security business.” He coughed as the waiter brought them the coffee.

“The sort of thing a con man would say.”

Again, he was forced to silence, cornered.

“Your daughter’s got a delightful power—”

“Ah, I was wondering if she’d told you. Please don’t use that like it’s a key to unlock the mysteries of my own approval. Abigail is infected. It’s a medical condition, not a political cause. I mean, look at her, look what’s become of her! I had to come over and see what she’d sunk to. Because I still care about her, you see.”

He hadn’t expected this. He’d just stared at her.

“Here she is, an exile from her home, because of what people there would say, living in a ghetto—”

“She came to New York for Broadway—!”

“An excuse for when you’ve lost a life of comfort and ease, and have been reduced to scraping a living by performing as a freak in a circus.”

“She is not a freak!”

“And neither are you.”

“No!”

“And that’s why you lied to me. When you told me you were normal.”

And suddenly Croyd was trying, and failing, to hold a dozen full cups of coffee. Like a clown. It burst all over the table. It stained the cloth, it covered his clothes, it burnt him. It missed Mum completely.

“Tell me everything,” she said. “I might be sympathetic to your plight.”

That’s all he told me of the conversation. It was only later I learned there was more to it. I stood there beside the ring with my phone in my hand, shaking. “I thought . . . she was proud of me,” I said. I managed to swallow down the end of that sentence. And then I hated myself almost as much as I hated her. “Where is she now?”

“Shopping. We’re still going to come to the show together. I don’t know why I said yes. I kept thinking about you—”

I hate being angry. I hate rows. I hate people grandstanding like that. I hate disruption. I hate that my mum drags me into all that. “I don’t want her here. I don’t want to see her—”

“Absolutely. You want it, I can get some of the guys to put her in the back of a cab and make sure she gets on a plane.”

“Yes. Yes, that’s great, do it!”

“Some of those guys I know. Who make sure of things. And you know she’s not going to make it easy, she’s going to push them. And then they might . . . reciprocate.”

“Fine.”

He gave up with that. He was just about yelling at me now. As if he was scared that neither of us could seem to find a way to stop the inevitability of all this. The inevitability. It only seems like that now. “And then, what, you’re estranged from her? Cut off? You don’t have a family no more?”

“I don’t now!”

I went backstage for costume and makeup. Alice, the makeup lady, had to ask me to relax my face, because she wasn’t going to be able to fill in the frown lines otherwise. I managed not to have her have to cope with tears. It was just basic stage makeup, and my costume was a deliberately ordinary frock and dark glasses. Covering up the tats hadn’t just been for my mother’s benefit.

Radha, in her colorful, loose-fitting stage costume, was waiting for me outside. She looked at me, understood something, and took my hands in hers. “Breathe,” she said.

I breathed.

“We’re doing this for the audience. We owe them our best performance.”

I managed to nod.

“Whatever this new crisis is, you have to put it behind you. For your own sake.”

I managed to share a smile with her. I was already there, actually. Or I thought it was. Performing is my home, and I was deciding it was also going to be my family. It and Croyd.

“But most important of all, remember this: If you don’t manage to put it out of your mind, and mess up up there, I will fucking kill you.”

And that was said with such an enormous grin on her face, and such steely eyes, that I was right back to being overawed again. And that took something serious in my brain and fixed it there for the future. Because that was professionalism. There it was. “Understudy,” I said, helplessly.

She shook her head. “No. Oh well. I’ll just have to name you.”

I couldn’t find anything to say.

I hurried out toward the side door to join the queue.

That was the plan, you see, for me to head into the venue with the rest of the audience, anonymously. I’d been provided with a ticket that would place me in just the right seat. I hesitated on the corner, looking at the line, worried that I’d join it at just the point Croyd and Mother did. But no, there they were, Croyd rolling his head to try and ease the tension, Mum looking pointedly at him and then all around, as if she was worried to be seen with him. As if the scales of right and wrong there were the other way round. Neither of them knew what the details of the act were going to be.

I joined the back of the queue and, desperately trying to put everything else out of mind, headed in with everyone else.

I took care to sense, as the four sides of bleachers around the ring filled up, if anyone else with, you know, powers, had entered. There were two, both deuces. That is, they had useless powers. One of them could turn her hands different colors, the other one had complete control over the style of his moustache. I relaxed, let my power harmlessly flirt with theirs. My palms ran through a range of hues, my top lip itched, but I didn’t let it sprout. If one of the audience had turned out to have a major power I couldn’t deal with the presence of, I had a number ready to call on my mobile, and they’d have been led out, with gifts and a refund, before Radha’s act. The circus authorities had obviously heard about my earliest experiences in professional theater.

I sat through the clowns, who were a fast-moving bundle of acrobatic sight gags that made the children and a lot of the adults in the audience squeal with laughter. None from me. My gaze, in the moments when the lights were up, had found Croyd and my mother in the crowd. She was looking prim, her mouth a line, suggesting a smile but not being one. I sat through a joker high wire act, the Flying Crustaceans, who used their pincers to snap from trapeze to trapeze. And I thought about me and, you know, love.

When I was in my teens, I’d been too focused on getting away from Dorset and the weight of history there to have much in the way of romance. By which I mean there was, you know, stuff, of the usual kind, involving cider and boys who drove tractors. But I always had one hand reaching out ready to extricate myself. I’d fallen in with Croyd like it was going to be the obvious, central relationship of my entire life, not, like these things seemed to be with some of my classmates at the School, a test drive, the first of maybe many. Maybe I was a bit old-fashioned like that. Made by my Mum. There was a terrible thought. I absolutely did not want to be. Had she been right that I’d run here not to something but from something? I thought about the times when my family had met other families from my parents’ class, what their looks had meant, what the lack of party invitations had meant, why I’d ended up only with boys who drove tractors and never those who bought them.

Well. Maybe the bitch was right about some things.

The lights went up on the ring once more, revealing Radha standing there. “Ladies and gentlemen!” she called out. And the audience was silent. And she didn’t need a mike. “You may have heard of me. You may think you know everything about me. You know I can do . . . this!” The lights flickered as the back-up generators kicked in, helping the grid handle the sudden demand for power. This was why the show had that sign outside saying no audience members with pacemakers allowed. The BAC had had to rent some serious megawattage to avoid blacking out whole city blocks. With a dramatic gesture, Radha’s body suddenly contorted and the space around her did too, like reality had just done a magic trick with a folded handkerchief. Her garment burst from her in a moment which managed to be (and I’m told you can see it slowed down to individual frames on YouTube) both alluring and modest at the same time. She spun to a halt on the spot, taking up much of the ring, in her new form, that of a full-sized Asiatic elephant.

“And,” continued her voice, now a recording being played over the speakers, “you probably know I can do . . . this!” And with an impossibly graceful upward leap, and a single flap of her enormous ears, the elephant that was Radha took to the air. She soared straight up, to the top of the big top, then managed, the band striking up a boisterous tune with shrieking electric guitar as she did so, to turn that into an elegant spiral, flashing over the audience, heading down and down, faster and faster. They started to applaud wildly, because most of them, being tourists, although they had probably heard of Radha’s power, wouldn’t have seen it live before. I didn’t applaud, though. Playing my part, I folded my arms over my chest, looking glum. This was not hard.

“But did you know,” the recording continued, “that I can also do . . . this!” And as she swung her third turn down toward me, she tensed her trunk, raised it above her head, and then straightened it suddenly in my direction.

The blast of water hit me right in the face.

At that same moment I let down my guard and let her power take me.

We’d practiced this move for weeks, with dummies in the seats around me. (Which had, actually, each been moved an inch farther away from mine.) I took the flight power a tiny instant before I took the transformation. My human feet sprang upward a moment before my body above them burst into its new elephantine shape. My carefully weakened clothes sprang apart, to reveal nothing much in that nanosecond, I really hoped, because I didn’t want that to become, you know, my signature move. To the audience, especially to those screaming in horror and glee nearby, it seemed that one of their number had suddenly exploded into being a flying elephant—

—who spiralled up to join, exactly as we’d rehearsed ten times a day, Radha, the two of us flying around the ring equidistantly. She was waving her trunk playfully, suggesting she could do it to many more of the audience too, and the clowns were running about putting up umbrellas over people. “No,” cried out the recording, “you’re quite safe. Ladies and gentlemen, may I present Abigail Baker, The Actor!” And there was applause as, perhaps with some relief, the audience remembered that I was that girl they’d heard about and, oh yes, they’d wondered what I was going to be doing in the show.

And she’d named me in that instant. Like something out of The Jungle Book. In the recording she’d made just before we went on. But I only really paid attention to that later.

Because as I sped above them, I kept looking at Croyd and Mother. Looking and looking. Round and round. Spiralling gradually downward. He was applauding, yelling, bellowing, loving me. Though he’d never used that word.

She was nodding, sighing, acknowledging that this was the best I could do in these sad circumstances. I was such a disappointment to her.

I couldn’t help it. I say that, but I know I could have. What was meant to happen now was that Radha and I were supposed to spiral in toward each other, clasp trunks, spin around until the moment it looked like we were going to fly up and hit the ceiling, then change back and fall, naked in the moment before the lights went out, into the net. Costumes would be thrown to us, and donned in the moment before we somersaulted out of the net and onto the sawdust to take our bows.

That’s what should have happened.

I got that expression of my mother’s locked into my head, bigger and bigger, on every circuit of the room. All her condescension, and all my guilt and anger, always in my way, time after time. And here I was doing this incredible, beautiful thing, here I was, strong and famous and adult, and it was never going to be acknowledged, not from this woman whose acknowledgment would have meant everything. To her, all this was shameful. My love was shameful. And so in the end was I.

And I proved her right.

I swear, I just wanted to knock that stupid hat off her head.

I swung deliberately an inch lower. I extended one of my enormous elephant feet as I saw her turning to look up toward me as I approached, looking perhaps a little bored now. Croyd realized a second before she did. He started to yell no.

Him looking scared in that second . . . him starting to cry out in horror, the sudden expression of the fear that had been hanging over us, the things we weren’t talking about . . . I think I must have instinctively reached out to him in that second, mentally. I think I must have connected us. For the last time. Because what his power really is, like he said . . . It’s sleeping.

I suddenly found a terrible shuddering fatigue grabbing my body. I realized, as the audience before me became a screaming dreamscape of surreal clowns, that I was somehow—

Falling asleep.

With my last conscious thought, I managed to use the power of flight that was about to leave me to throw myself sideways.

I could feel myself spinning as time slowed down to a crawl. It was half a dream, half adrenaline trying desperately to keep me awake as I spun toward those hard bleachers and the flesh and bone of anyone I might connect with in a high-speed crash.

Something grabbed me from behind. And threw me with the strength of an elephant.

And there was Croyd throwing himself forward out of the seats, heaving clowns out of the way, and diving for the safety net. For so much more safety net. Than there had been. In a different place. And he was right underneath me now! If I was still an elephant when I landed—!

I woke up in a hospital. I scrambled up, shouting, demanding to know if everyone was all right—! And standing there at the end of my bed wasn’t Croyd or my mother . . . just Radha.

“Nobody got hurt,” she said. “You included.”

After a moment I was able to talk again. “That was sheer luck,” I said finally. “It was all my fault.”

“Yes,” she said.

“Understudy,” I said, starting to cry. Because it hadn’t been Croyd who had nearly hurt someone in a careless rage.

“Yes,” she said. And it turned out that had been all she’d been there to say. Because she headed for the door. A moment later, Croyd and Mum entered. Like she’d told them I’d said it was okay. They both looked horribly caring and fearful at me. I felt like I was twelve or something.

“My darling,” said Mum, and meant it. “My darling, thank God.”

The look on Croyd’s face said he hadn’t told her what I’d been trying to do. He looked more tired than I’d ever seen him.

They let me go home that same day. I was clearly not in shock, having been asleep at the moment when, thankfully as a human being, I’d been caught in Croyd’s arms. Mother stayed beside me, occasionally looking at me as if to ask if it was all right she was there. I wondered if she’d somehow intuited that Croyd had told me what she’d said. She looked so frail, suddenly. She looked lost in a foreign country. She wasn’t proud of me, but she was afraid for me. It weirdly seemed now like even that much must be difficult for such a small woman to manage. She and Croyd were careful with each other. We went back to my place in the same taxi. We didn’t talk.

I found a message on my answerphone from the owner of the circus, asking me to call as soon as I felt able to, to talk about my “employment options.”

I went into the kitchen space with Croyd, wondering what Mum would make of the tea we had over here. Croyd held me. He was quaking. I heard a noise from the other room. It sounded like a sob. And then the door opened.

I ran out into the stairwell, but Mum was already on her way down, as fast as her heels could take her. “I can’t, darling,” she called, before I could shout, “I’ll come and see you tomorrow.” And then she was gone.

Croyd sat on the sofa just staring at me. He looked desperately sick. “I thought . . . I thought . . .” He didn’t look as if he could think anything. He looked like he was about to have a heart attack. Saving me had taken all the strength he had left. His eyes were half in a dream.

I decided.

I went to the kitchen and made him a cup of very strong coffee. In it, I dropped the sleeping pill I’d taken from my mother’s purse.

He took a few sips of it, then as soon as he could, threw back the whole mug. He could hardly talk. He was desperately holding on. I put my arms around him, and rested his head on my shoulder, and hoped that I hadn’t just committed murder. To go alongside all my other guilt that day. He tried to fight the feeling, tried to fight me, but finally, with an exhalation, his head slumped against mine and he was asleep.

I put him to bed. I piled food beside it, ready for when and if he woke: boxes of Hostess Twinkies. I lay beside him, trying not to think about the evening performance that was taking place amongst all those lights out there, without me. I wondered if I’d finished off my life here alongside his. I kept checking to see that he was breathing. Sometime in the early hours I fell asleep myself.

I woke and he was in the exact same position, still asleep, still breathing. I put a little water in his mouth. I checked my phone and found a message from Mum. She sounded calm, lost. She’d meet me at the same place she’d met Croyd. She said one o’clock, as if leaving it up to me to arrive or not, or controlling me still. One or the other.

I looked at Croyd and decided that he would either wake or he wouldn’t. It might be days. I had to see her. I wasn’t exactly sure what for.

We sat in the low angled sunlight of the coffee shop. She looked momentarily pleased to see me. Then she locked that expression away. “How is he?” she asked.

“Asleep.”

“Yes. I thought it would be soon.”

“He told you about his power?”

“Yes. Did he tell you what I said?”

“Yes.”

She closed her eyes. “When I’d heard everything, I told him he reminded me of the wide boys my father used to hang around with. He was of that generation, and of that type. I asked him how he could ever be sure that he wouldn’t hurt you in a drug-induced rage. My father, after all, gave my mother a black eye occasionally. And so that is something I would never allow, for myself or for you. I asked him that simple question, and he flung the table aside, bellowed at me, threw cups and plates at me, until I was quivering.” She looked suddenly ashen at me. “Oh. He didn’t tell you that part.”

I was furious with her all over again. But I held it in. “I believe you,” I said. “But he would never have hurt you.”

“I understood that at the time, I think. And I became convinced of that when I saw him risk his life to save you. The elephant almost crushed him, you know—”

“You mean I did.”

“I told him he was too old for you. That you could never keep up with him. That you still needed to grow. That he would get frustrated at that, and there would come a time for the black eye. He stopped yelling. He finally started listening to me.”

I knew my apartment was empty before I entered. I found mucous and scales and what might have been feathers on the bed. I fell back against the wall.

He was alive.

But he had not stayed. He had not gone out to find a pizza or anything storybook like that.

He wasn’t coming back.

I was sure he had done it for me. But perhaps it was apt punishment also. I had, after all, controlled the most important decision he made. Perhaps, that day, we had saved each other’s lives and parted because of it. Or perhaps we were just victims of the way the world is still made. I haven’t decided yet.

I tried to stop myself, but I gave in. I tried to find him. But I’d left it too long. And he’s good at not being found. I might have seen him, amongst the jokers passing me. I kept looking, for a while. I didn’t know what he looked like.

Mum and I spent the next few days together. I told her Croyd had gone. She nodded. We didn’t talk about what had happened. Or anything else meaningful. We talked about the weather, which was getting colder. We talked about New York, which she’d started to gaze at, from out of the window.

Finally, it was time for her to go home. She asked me when I had to return to school. I told her I still had two weeks. I thought she was about to offer me money, but she thought better of it. She kissed me on the cheek and I smelt the same perfume that I associated with what I’d fled, and felt the age of her skin on mine. I gave her some of the many boxes of Hostess Twinkies I still had lying around, which I was sure she’d give all of to Maxine. I was sure for many reasons.

The media coverage was minor to nonexistent, an accident to an increasingly minor celebrity. A run of shows cancelled, understandably. I rejoined the School much as I’d left it.

I’ve talked to Mother on the phone twice since then. She’s more like her old self. Which is either normal, or evil, or scared, depending on the background she’s seen against. The weather over there is much as it is here, getting colder. The aunts are fine. Thanks for asking.

As the snows came to New York, I realized that I’d stopped looking for Croyd in every crowd of jokers. That I’m sure I will see him again. I call myself The Understudy in ace circles now, and will until I feel justified doing otherwise. I don’t know how that could happen. But I know it might.

I’ve finished crying, anyway. Telling this story cleared something away for me. I don’t know if I entirely wanted it cleared. But it has been.

There’s no justice to any of this. One day I may end up taking care of my mother. She will never apologize for anything. I’m not sure I could ever be sure enough to insist she should. The battles of our adolescence can never be won.

*Possibly in Fort Freak, the latest Wild Cards book, in which Abigail makes her first appearance.

“The Elephant in the Room” copyright © 2013 by Paul Cornell

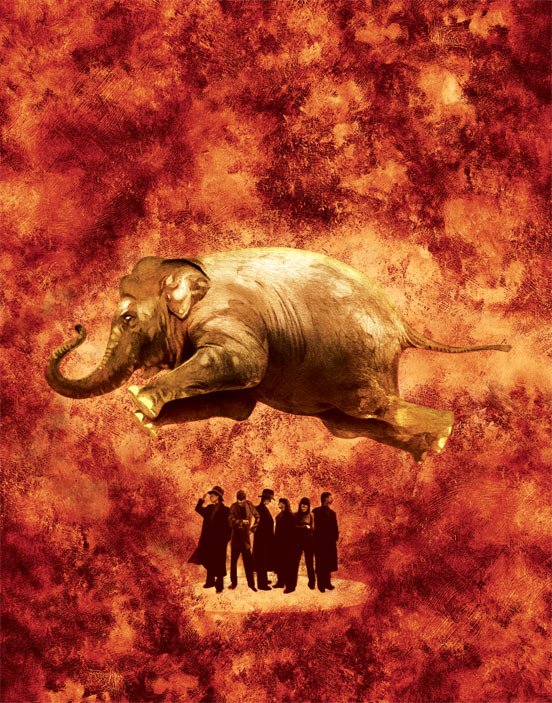

Art copyright © 2013 by John Picacio